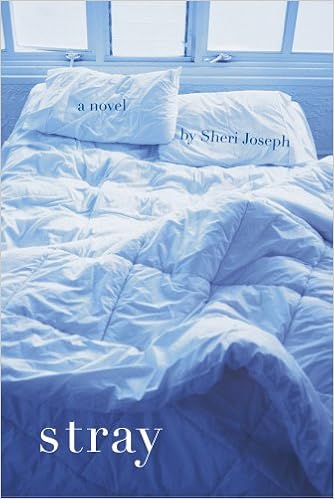

Sheri Joseph, Stray. San Francisco: MacAdam & Cage, 2007.

Publié en février 2007 (même si le copyright indique 2006), Stray est le deuxième roman de Sheri Joseph. En général, le terme qui fait titre est utilisé comme adjectif pour signifier l’errance et l’abandon : a stray dog, a stray teenager, etc. On pourrait donc suggérer une traduction comme À l’abandon ou Le garçon déchu (mais ce second titre est un peu trop sensationnaliste). Dans une interview, l'auteur suggère de considérer ce mot comme une contraction de straight et gay, emblématique de l'un de ses personnages ! En tout cas, il importe de signaler que le livre fait suite à Bear Me Safely Over (Prends moi par la main) dont il est le sequel, comme diraient les scénaristes. D’ailleurs, je conseillerais plutôt de commencer par le précédent avant d’entamer la lecture de Stray. De la même façon, je recommande à ceux de mes lecteurs qui n’ont pas lu Bear Me Safely Over (en français ou en anglais) mais qui souhaiteraient le faire de ne pas aller trop loin dans la lecture de ce post, au risque de voir éventés un certain nombre de rebondissements que l’on peut avoir du plaisir à suivre au fil de la lecture.

Publié en février 2007 (même si le copyright indique 2006), Stray est le deuxième roman de Sheri Joseph. En général, le terme qui fait titre est utilisé comme adjectif pour signifier l’errance et l’abandon : a stray dog, a stray teenager, etc. On pourrait donc suggérer une traduction comme À l’abandon ou Le garçon déchu (mais ce second titre est un peu trop sensationnaliste). Dans une interview, l'auteur suggère de considérer ce mot comme une contraction de straight et gay, emblématique de l'un de ses personnages ! En tout cas, il importe de signaler que le livre fait suite à Bear Me Safely Over (Prends moi par la main) dont il est le sequel, comme diraient les scénaristes. D’ailleurs, je conseillerais plutôt de commencer par le précédent avant d’entamer la lecture de Stray. De la même façon, je recommande à ceux de mes lecteurs qui n’ont pas lu Bear Me Safely Over (en français ou en anglais) mais qui souhaiteraient le faire de ne pas aller trop loin dans la lecture de ce post, au risque de voir éventés un certain nombre de rebondissements que l’on peut avoir du plaisir à suivre au fil de la lecture.

Car Sheri Joseph est indéniablement une romancière, avec ce que cela implique de plaisir immédiat dans l’exposition progressive d’une histoire. On retrouve deux personnages essentiels de Bear Me Safely Over : Paul Foster et Kent McKutcheon, qui forment un triangle avec Maggie (Magdalena) Schwartzentruber, personnage nouveau dans la « saga » de Paul et Kent. Alors que le roman précédent était choral, avec une temporalité compliquée et des narrateurs multiples, celui-ci est d’une simplicité évangélique. Il se déroule quasiment en continu durant six mois, lors de la dernière année de college (premier cycle universitaire) de Paul Foster. Le livre s’ouvre et se ferme par un épisode de week-end en Floride, partagé par les deux personnages masculins, dessinant une sorte de parenthèse dans leurs existences respectives.

It was a compulsion: at every mile marker they passed on the drive to Florida, he flicked his wedding band with a thumb nail. He kept his eyes on the road. Paul’s voice was a soft continuous monologue from the passenger seat, remarking on the landscape, laughing, luring him by slow degrees into remember and we’ve always and us and our, and by the time they reached the gulf-side condo where they would spend the weekend, the sound of that voice had curled up to purr in Kent’s ear, louder than the waves eight floors below their rooms. He felt it as a vibration from within his own body rather than without, now that Paul had gone out on the balcony to look down at the beach.

Standing in the dim interior of someone else’s vacation home — a living room with glass-topped tables and pastel furniture and framed square prints of seashells on the walls — he gave the ring a twist. Outside, Paul’s blond head was crowned in a brilliance of late-day sun, his hands braced on the wrought-iron rail, and the same chill wind that carried through the open doorway the faint shouts of children and gulls ruffled the shirt along Paul’s shoulders and flattened it to the lean contours of his torso. He was twenty-one. In three years, it seemed he had changed little, same downy stem of a neck and stuck-out ears flushed deep pink along the rims. If an inch taller now, broader in the shoulder, his body was still cut as much for Peter Pan as for Hamlet, the role he claimed to have played in a college production the year before. But he was not the pliable thing that had lived in Kent’s imagination over the missing time, and it was good to have a minute to adjust to the reality of him — Paul, there, in his willful and difficult flesh.

Probably he was waiting to be coaxed back inside. One foot was hooked behind the other, his face canted toward the beach where there were only a few off-season tourists like themselves —couples strolling the winter sand, a family or two on blankets. Children, yearning for a chance in swim, dashed in test the surf with their toes again, and again, though it was January and they must have known the water would never be warm enough.

Kent tuned to the inner vibration that made his empty hands at his sides quiver. It sounded like wrong, wrong, wrong, timed to Paul’s steps as he returned inside. To be here was to be already out of control. But he had a plan, insubstantial and fine as a wire. To indulge. To remain detached.

“You’re married,” Paul said. They were kissing, fumbling with buttons.

“I know that.” (incipit, p. 1-2)

Stray se déroule donc trois ans après la fin de Bear Me Safely Over. On découvre très rapidement que les deux héros se retrouvent au début de ce nouveau roman bien longtemps après une séparation très douloureuse : Paul a quitté Kent alors qu’ils vivaient en couple à Athens (en Géorgie). L’un puis l’autre ont finalement élu domicile (ou trouvé refuge ?) à Atlanta. Paul a entamé des études de théâtre auprès de Bernard Falk, un lointain disciple de Stanislavskiï, dont il est devenu l’amant puis le protégé. Kent, quant à lui, a rencontré Maggie, et auprès d’elle, il a retrouvé une existence plus conforme à son idée de la vie. Il a renoncé à sa carrière de guitariste et travaillote, davantage concerné par sa vocation d’homme au foyer. Maggie, elle, est avocate, et a dévoué sa vie à défendre les condamnés à mort. Elle appartient à l’église Mennonite, une dénomination assez proche des Amishs, à cette différence majeure que les Mennonites sont « dans le monde » et ne refusent pas la modernité. Maggie est un personnage extrêmement attachant, qui me rappelle Sidra Ballard.

In the kitchen, Lila handed her a loaf wrapped in foil and red ribbon, still warm, along with a second in plain foil. “That one’s for you,” she said, of the ribbonless package. “To take home to your poor starving husband.”

Maggie set them on the counter. “Wow, check out the cut!” Two-handed, she reached over her sister’s seven-months-pregnant belly to fluff her newly short hair. As children, their hair had grown long and straight, past their hips — they hadn’t been allowed to cut it. Combing and braiding had been a daily chore. Now, as adults, they seemed to be dueling with shorter and shorter cuts. Maggie’s dark hair kicked out in wisps along her neck. Lila’s, lighter and russet-tinted with flecks of gray, was now capped close to her head and feathered back on one side.

“Don’t copy it,” Maggie’s niece, Chloe, admonished her from the table where she was doing homework. “Yours is cute the way it is. Hers is too short, don’t you think?”

She wasn’t really asking. Ever since Chloe had hit puberty, she had put herself in charge of all family issues involving taste and propriety. She had also decided entirely on her own that Mennonite was cool. For the sake of family and tradition, she said, not just for beauty, she wore her honey-brown hair the way they had as girls. Today it swept loose over her shoulders and past the seat of her chair. To conceal her braces, she spoke almost always in a kind of terse, pointed mumble, but it was a vanity that she had managed to package into an unsmiling diva persona that worked beautifully for her — as if the world were just a little too vulgar to warrant her full emotional engagement.

“I don’t copy her, I’ll have you know,” Maggie reminded Chloe. “She copies me.”

“Oh, please!” Lila said. “Who got married first? Who moved to Atlanta first?” None of this sparring was exactly fair, since Lila was eight years older. She patted the mound of her belly. “You’ll have one of these next.”

Chloe snorted and said, “Yeah, you’re falling way behind there,” as if the one in progress were Lila’s tenth and not her third.

Maggie sat at the table. The teapot whistled and Lila filled two mugs. The kitchen was already aromatic with the fresh-herbed pork roast in the oven. “I think I’m not having any,” she said, kind of experimentally. “Of those, I mean.”

“Good for you!” Chloe barked. “The world is overpopulated. But try telling some people that, who can’t even be bothered to eat vegetarian.”

“I have too much to do,” Maggie said, a little insistent though Lila hadn’t said a word. “There are so many messed up people in this city— I really think I have my hands full as it is without making more of them.”

“Amen, sister,” Chloe muttered, pencil scratching along her paper. “You go, girl.”

Lila considered her, mouth a straight line, and Maggie knew she was once again being assessed for damage. But Lila wouldn’t open the door to past traumas with Chloe in the room, and she shrugged herself back into a lighter mood. “You don’t mean that. You’re just being outlandish, as usual. You’re young!”

“Always younger than you. But not that young.” She ran her hands back through her hair, which felt too long suddenly, unruly. “I’m serious, when am I going to change a diaper, huh? I don’t really have a big interest in diapers, to be honest. I’d have to hire a nanny and that’s no way to raise a kid.”

“I’ll be your nanny,” Chloe said. “I need the money.”

“It’s just not me.” She felt the need now to reassure her sister that she was fine. “The mom thing. I’m a lawyer. My house has”— she searched Lila’s kitchen, her hand-sewn curtains and terra-cotta tile— “dirt in it. And very rarely any bread to speak of.”

“Have you mentioned this to Kent?”

This took her off guard. “Kent? Why?”

Lila pursed her mouth primly. “Well, I think he might want kids.”

She scoffed, and then looked at Lila harder. “Really?” But the idea was ridiculous. “Why, because he’s a guy? This is your theory, that all men have some biological drive to reproduce?”

Lila sipped her tea. “When they get married? I’d say, usually. They’re thinking it somewhere. Besides, he’s got that whole dad vibe going on. You know, like at family picnics, that manly grill-guy-giving-piggy-back-rides-and-holding-the-baby thing.”

“But we aren’t that way,” Maggie said, though it was hard to find the words for what she meant — especially without insulting the whole child-bearing endeavor. We’re complete in ourselves, she wanted to say, of her fragile one-year union. “Not all marriages have to be like that. They can be about other things, can’t they?” (p. 37-39)

Davantage encore que son prédécesseur, Stray est un roman caméral, qui se déploie en un nombre extrêmement restreint de lieux (les appartements de Bernard, la maison de Kent et Maggie, celle de sa sœur, plus quelques autres), un nombre non moins restreint de personnages (grosso modo de sept à vingt, si l’on compte seulement les principaux, ou si l’on adjoint les rares figurants). Plus encore, tout tourne autour du trio Paul/Kent/Maggie, qui tiennent les premiers rôles. Huis-clos ? Le qualificatif serait tentant — sauf que justement les personnages (à commencer par la jeune femme) sont ouverts sur le monde, même s’ils demeurent attachés à quelques lieux d’Atlanta. Rien ne suggère un quelconque enfermement. Simplement ce qui intéresse la romancière est la géographie changeante des sentiments, qui ne se préoccupe qu’accessoirement d’un décor. Ici encore, très peu de descriptions, et toujours nettement circonscrites, localisées. Ce dispositif est mis en abyme par l’activité théâtrale de Paul, dans laquelle se reflète l’une des questions majeures du roman : la vie ressemble-t-elle à une pièce de théâtre ? Question à laquelle Sheri Joseph répond, il me semble, entièrement par la négative !

En effet, Stray a des allures de tragédie (ou de roman noir). Et d’ailleurs, à mesure que l’histoire avance, les personnages se trouvent enserrés dans une intrigue de plus en plus inextricable. Au départ, on découvre donc qu’après une longue séparation Paul et Kent se sont retrouvés dans une bibliothèque, et que le désir sexuel entre eux est encore extrêmement vif. Lorsque le personnage de Bernard Falk apparaît, on apprend qu’il est atteint d’un cancer en phase terminale. Il apparaît aussi que Kent n’a de cesse que d’expulser Paul de sa vie et que celui-ci vit son avenir comme un gouffre sans fond, entre le rejet de l’homme qu’il a toujours aimé et l’affection encombrante de quinquagénaires qui s’ingénient à le « protéger ». Et quand un enchaînement de circonstances le propulse dans la vie de Maggie et que peu de temps après Bernard meurt dans des circonstances tragiques, l’étau se resserre lentement autour du cou de Paul… Progressivement, Stray devient une sorte de thriller psychologique, dans lequel une trame policière vient s’entremêler avec un écheveau psychologique. La montée en puissance du suspense est tout à fait redoutable. Le lecteur se retrouve une nouvelle fois placé devant un abîme qui menace l’existence de Paul, et peut également contaminer Kent et Maggie.

Plus classique dans sa narration, Stray est nettement plus sombre que Bear Me Safely Over, roman qui semblait empreint d’un humanisme optimiste. Ici, au contraire, Sheri Joseph fait surgir des tâches d’ombre un peu partout, dessinant suggestivement les lâchetés des uns et l’aveuglement des autres. Les personnages s’ingénient à ne pas se comprendre et leurs combats, aussi beaux soient-ils, ressemblent à un perpétuel déni. Dans cette farandole d’illusions amères, de pulsions mesquines, seul Paul demeure à peu près indemne, même s’il n’est pas le dernier à s’illusionner. À bien des égards, le roman est un très beau portrait de jeune homme peu à peu saisi par une maturité rayonnante.

Comme toujours avec les romans en anglais, j’éprouve des scrupules à émettre des analyses stylistiques, tant j’ai le sentiment qu’il me manquera toujours une partie du génie de la langue. Je peux juste dire que ce gros roman de 444 pages est passionnant, écrit dans une langue riche et alerte. J’ai déjà souligné le talent de dialoguiste de Sheri Joseph. Cela se confirme ici, outre une inclinaison pour une sorte de pastiche à la manière de Patricia Highsmith et une ironie latente, comme moirée. Au-delà de ce qui se passe et se pense, on devine la romancière placée en léger retrait, encore moins dupe que quiconque de cette dramaturgie parfois violente. Le livre a un double-fond comme une pièce de théâtre peut avoir un hors-scène, et c’est dans cet ailleurs que le lecteur trouve les ressources les plus précieuses.

J'en arrive enfin à mon préféré, un acteur qui est déjà immense, alors qu'il est encore très jeune. Paul Dano est né le 19 juin 1983 selon les sites de fan et un an plus tard selon IMDb... Ce qui lui fait bientôt 24 ou 25 ans selon les cas... Non content de faire l'acteur, il joue aussi dans un groupe de rock tout à fait fréquentable, Mook. Pour les curieux, le groupe a une page sur Myspace (facile à trouver).

J'en arrive enfin à mon préféré, un acteur qui est déjà immense, alors qu'il est encore très jeune. Paul Dano est né le 19 juin 1983 selon les sites de fan et un an plus tard selon IMDb... Ce qui lui fait bientôt 24 ou 25 ans selon les cas... Non content de faire l'acteur, il joue aussi dans un groupe de rock tout à fait fréquentable, Mook. Pour les curieux, le groupe a une page sur Myspace (facile à trouver).